This is a follow-up to my last post on Hands-On Winemaking. Last September I put up a post on my Westwood blog where I attempted to define my personal winegrowing philosophy as "Pre-Emptive Minimalism".

In a nutshell, following this approach means to 1) do nothing I don't have to, and 2)to do nothing that forces me to do extra work later. In the context of the last post I would call this "Interventionist Minimalism" in contrast to minimal intervention.

Friday, June 27, 2008

Saturday, June 14, 2008

Hands-On Winemaking

My friend Greg Snell recently posted to his blog about "non-interventionist" winemaking and the WinePod. I will take this opportunity to weigh in on the subject.

What on earth does someone mean when they talk about "non-interventionist winemaking"? Where did this term come from? I'm not the first person to ask these questions. Check out Eric Asimov's piece in the NY times from October 2006. I think it may be that the term first arose in the film "Mondovino" which, for dramatic effect, built its narrative around the differences between the "...old world and new, simple peasants and billionaires, and between the local and artisanal styles of wine production and the multinational and mass-produced ones."

Award-winning New Zealand winemaker and writer Drew Tuckwell put it as succinctly as such a vague and useless concept might possibly be clarified: "Non interventionist winemaking is not easy to explain. There are no defined or common rules. It is essentially a very natural form of winemaking ... where, in general terms, winemakers resist the use of modern technology and simply allow the wines to express the terroir of the vineyard." (1) Emphasis mine.

My sainted Dallas-bred grandmother had a term for this kind of marketing-speak: "horse-puckey".

The craft of winemaking is the transformation of grapes with alchemist skill. For centuries the French have applied the terms "elevage" and "affinage" to the winemaking process. The winemaker facilitates the birth of the wine, and then raises it and refines it into something which, if not always transcendent and sublime, is at least palatable. I believe the most apt analogy for winemaking is child-rearing. I for one don't believe that child rearing can be at all non-interventionist. And neither can winemaking be.

I shall step on a slightly taller soapbox to proclaim: I believe that ALL wines – artisanal and mass-produced alike – are valid expressions of the grape, and of the winemaker's craft. There is no way to define a cutoff between these arbitrary classifications; wines are produced along a technological contiuum.

On the other hand, all wines are not created equal. There are distinctions between the aromas and tastes of wines made by hand and those produced by machine that are no more arbitrary or subtle than the differences between, say, Redwood Hill Farm crottin and processed American cheese spread, or Boont Amber Ale and Bud. But there is no doubt that the makers of the crottin and the ale are interventionist to a fault in crafting their products. So are ALL winemakers worthy of the title.

For contrast, let me paint a scenario of the least-interventionist winemaking I can imagine. Find some grapes – they must be wild, or escapees from cultivation, un-pruned and otherwise un-farmed. Pay no attention to the mildew, bird damage and rot. Taste them to see if they are ripe, and try to forget that professionals with decades of experience sometimes misjudge ripeness by taste. Pick them anyway.

Put these natural wonders in a garbage pail in the garage – don't worry if the pail is clean or not, or how hot or cold the space is. Intervene to the extent of crushing the grapes by foot. Step away at this point, intervention complete – the grapes will ferment. But at least go so far as to cover the pail before turning out the lights. Come back in a month or so, lift the pail and make a small hole in the bottom for the liquid to drain out. Intervene again to push on the mass inside the pail to press as much liquid out as possible. Collect, taste and savor.

I can say from personal experience that the results will not be palatable.

I can also say that there is not a capital-poor winemaker worth the title that has not wished for a centrifuge (for clarification), a spinning cone (for alcohol reduction), or for ion-exchange (to remove volatile acidity) at some point in their career. In my opinion, any winemaker that can say they are "non-interventionist" with a straight face, or at least without a little lurch of self-loathing in the pit of the stomach, is a charlatan or worse – delusional.

Given the choice between a garbage pail and the WinePod, I'll take the Pod thanks. I can make better wine in the WinePod. Doesn't make me a mass-producer – the wines are still hand-made. Just don't call me "non-interventionist".

What on earth does someone mean when they talk about "non-interventionist winemaking"? Where did this term come from? I'm not the first person to ask these questions. Check out Eric Asimov's piece in the NY times from October 2006. I think it may be that the term first arose in the film "Mondovino" which, for dramatic effect, built its narrative around the differences between the "...old world and new, simple peasants and billionaires, and between the local and artisanal styles of wine production and the multinational and mass-produced ones."

Award-winning New Zealand winemaker and writer Drew Tuckwell put it as succinctly as such a vague and useless concept might possibly be clarified: "Non interventionist winemaking is not easy to explain. There are no defined or common rules. It is essentially a very natural form of winemaking ... where, in general terms, winemakers resist the use of modern technology and simply allow the wines to express the terroir of the vineyard." (1) Emphasis mine.

My sainted Dallas-bred grandmother had a term for this kind of marketing-speak: "horse-puckey".

The craft of winemaking is the transformation of grapes with alchemist skill. For centuries the French have applied the terms "elevage" and "affinage" to the winemaking process. The winemaker facilitates the birth of the wine, and then raises it and refines it into something which, if not always transcendent and sublime, is at least palatable. I believe the most apt analogy for winemaking is child-rearing. I for one don't believe that child rearing can be at all non-interventionist. And neither can winemaking be.

I shall step on a slightly taller soapbox to proclaim: I believe that ALL wines – artisanal and mass-produced alike – are valid expressions of the grape, and of the winemaker's craft. There is no way to define a cutoff between these arbitrary classifications; wines are produced along a technological contiuum.

On the other hand, all wines are not created equal. There are distinctions between the aromas and tastes of wines made by hand and those produced by machine that are no more arbitrary or subtle than the differences between, say, Redwood Hill Farm crottin and processed American cheese spread, or Boont Amber Ale and Bud. But there is no doubt that the makers of the crottin and the ale are interventionist to a fault in crafting their products. So are ALL winemakers worthy of the title.

For contrast, let me paint a scenario of the least-interventionist winemaking I can imagine. Find some grapes – they must be wild, or escapees from cultivation, un-pruned and otherwise un-farmed. Pay no attention to the mildew, bird damage and rot. Taste them to see if they are ripe, and try to forget that professionals with decades of experience sometimes misjudge ripeness by taste. Pick them anyway.

Put these natural wonders in a garbage pail in the garage – don't worry if the pail is clean or not, or how hot or cold the space is. Intervene to the extent of crushing the grapes by foot. Step away at this point, intervention complete – the grapes will ferment. But at least go so far as to cover the pail before turning out the lights. Come back in a month or so, lift the pail and make a small hole in the bottom for the liquid to drain out. Intervene again to push on the mass inside the pail to press as much liquid out as possible. Collect, taste and savor.

I can say from personal experience that the results will not be palatable.

I can also say that there is not a capital-poor winemaker worth the title that has not wished for a centrifuge (for clarification), a spinning cone (for alcohol reduction), or for ion-exchange (to remove volatile acidity) at some point in their career. In my opinion, any winemaker that can say they are "non-interventionist" with a straight face, or at least without a little lurch of self-loathing in the pit of the stomach, is a charlatan or worse – delusional.

Given the choice between a garbage pail and the WinePod, I'll take the Pod thanks. I can make better wine in the WinePod. Doesn't make me a mass-producer – the wines are still hand-made. Just don't call me "non-interventionist".

Saturday, June 7, 2008

Catching Up With The Roberts Road Pinot

The Sangiacomo Roberts Road Pinot lot finally completed alcoholic fermentation after the re-inoculation on 4/7.

My personal cutoff for "doneness" on alcoholic fermentation is 1.00 g/L, though I prefer to see on the order of 1/10th that number before I inoculate for malolactic – which is sort of what I did.

On 5/15/08 I inoculated the Pinot in barrel and carboy with 2.5 grams of Enoferm Alpha malolactic culture, prepared according to directions.

| glu+fru | malic | ||

| 03/28/08 | 3.94 | 1.33 | g/L |

| 04/03/08 | 3.05 | ---- | g/L |

| 04/14/08 | 1.18 | 1.22 | g/L |

| 05/02/08 | 0.20 | 1.09 | g/L |

On 5/15/08 I inoculated the Pinot in barrel and carboy with 2.5 grams of Enoferm Alpha malolactic culture, prepared according to directions.

Thursday, June 5, 2008

Finishing Off The Syrah Fermentation

May was a very busy month for me and I was not able to devote the time I wanted to maintaining this blog. It is time to catch up and so this is likely to be a long post.

I pressed off the Annadel Syrah on 5/1/08 after a full 30 days of maceration at elevated temperature (73° F) – if there was a question in anyone's mind, it was my intention to see how far I could push this protocol.

Jumping ahead a little, in my opinion the wine turned out very well, analytically and organoleptically. So since I didn't "break it" with a full month of maceration I can't say that I have pushed the procedure to its absolute limit. But what I learned is that I can be more sanguine about recommending longer maceration in the Pod – at least up to this now-defined point, and with these grapes.

I pressed the Syrah as I have the other lots: first with automatic pressing on the "heavy" setting (present on this Pod beta unit – likely not on shipping units) until done, then on manual every minute, then every 2 minutes, then every 5 minutes, until the press shuts off immediately on startup. Also as before, I racked the wine from the Pod into buckets, cleaned the Pod, and racked the wine back in. The yield was about 11 gallons. I set the temperature of the Pod to 65° F.

I pulled a sample for the lab; results of the analysis:

My personal threshold for malolactic "doneness" is 0.30 g/L so this wine is done enough. The V.A. has crept up a tiny bit since the end of alcoholic fermentation (from 0.26 g/L – almost within analytical error) supporting that the long extension of maceration didn't oxidize the wine appreciably. From a philosophical standpoint the pH is higher than I want it to be, though the wine does not taste fat, soapy, or bitter.

On 5/4/08 I set the temperature of the Pod to 60° F. The next day I stirred in 20 grams of tartaric acid (0.5 g/L) and 5 grams of Efferbaktol granules (about 48 ppm of SO2).

The Syrah settled in the Pod at 60° F for nearly two weeks. On 5/16/08 I racked the wine to glass carboys (7, 2 and 1 gallon) with the extra going into two 750 mL bottles. Total yield of clear wine after racking was 10.4 gallons.

In my commercial wine production I have found that Syrah benefits from spending some time in tank after the first racking, before going to barrels. It is my intention to leave this WinePod Syrah in glass for a while before I put it into wood.

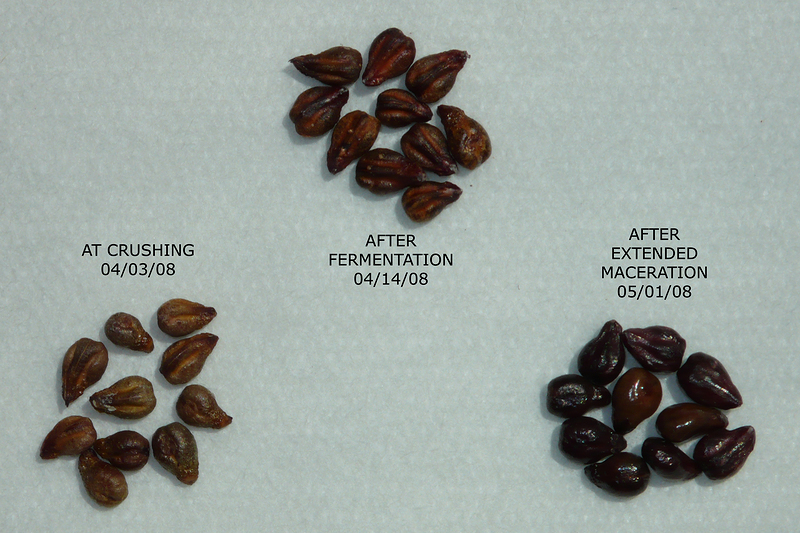

Another thing I wanted to do with this Syrah ferment was collect seeds to illustrate the changes that occur during extended maceration.

The seeds in the middle were pulled from inside berries at the end of the yeast fermentation. Notice that they are darker and redder, but not uniformly colored.

The seeds on the right were removed from berries in the press cake after taking it out of the Pod. Notice how they have turned darker, and though not all of them are exactly the same dark shade the color is uniform on each. These are the visual qualities I look for in the seeds on completion of extended maceration.

I pressed off the Annadel Syrah on 5/1/08 after a full 30 days of maceration at elevated temperature (73° F) – if there was a question in anyone's mind, it was my intention to see how far I could push this protocol.

Jumping ahead a little, in my opinion the wine turned out very well, analytically and organoleptically. So since I didn't "break it" with a full month of maceration I can't say that I have pushed the procedure to its absolute limit. But what I learned is that I can be more sanguine about recommending longer maceration in the Pod – at least up to this now-defined point, and with these grapes.

I pressed the Syrah as I have the other lots: first with automatic pressing on the "heavy" setting (present on this Pod beta unit – likely not on shipping units) until done, then on manual every minute, then every 2 minutes, then every 5 minutes, until the press shuts off immediately on startup. Also as before, I racked the wine from the Pod into buckets, cleaned the Pod, and racked the wine back in. The yield was about 11 gallons. I set the temperature of the Pod to 65° F.

I pulled a sample for the lab; results of the analysis:

| pH | 3.94 | |

| Malic Acid | 0.13 | g/L |

| Volatile Acidity | 0.38 | g/L |

On 5/4/08 I set the temperature of the Pod to 60° F. The next day I stirred in 20 grams of tartaric acid (0.5 g/L) and 5 grams of Efferbaktol granules (about 48 ppm of SO2).

The Syrah settled in the Pod at 60° F for nearly two weeks. On 5/16/08 I racked the wine to glass carboys (7, 2 and 1 gallon) with the extra going into two 750 mL bottles. Total yield of clear wine after racking was 10.4 gallons.

In my commercial wine production I have found that Syrah benefits from spending some time in tank after the first racking, before going to barrels. It is my intention to leave this WinePod Syrah in glass for a while before I put it into wood.

Another thing I wanted to do with this Syrah ferment was collect seeds to illustrate the changes that occur during extended maceration.

Click on the image above for larger 800 px image

Click on the image above for larger 800 px image

The seeds in the middle were pulled from inside berries at the end of the yeast fermentation. Notice that they are darker and redder, but not uniformly colored.

The seeds on the right were removed from berries in the press cake after taking it out of the Pod. Notice how they have turned darker, and though not all of them are exactly the same dark shade the color is uniform on each. These are the visual qualities I look for in the seeds on completion of extended maceration.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)